This may be the longest article I have written. For good reason though. China is a big place and it takes a lot of words to even scratch the surface.

It doesn’t help that western media reporting on the recent tech crackdown has been one-dimensional i.e. not a lot more informative than the bad guys (Chinese government) beating up on the good guys (infotech firms).

But like any real story, the villains and the heroes are a lot more complex.

What one needs is a framework to understand current events and capture the underlying themes in China investing. The one that makes the most sense (to me) is “ESG”. As you’d expect, this is not exactly the same as the liberal-progressive ESG we are used to.

But the fact is that under Xi, China is hyper-focused on achieving objectives that fit rather well under Environmental, Social and Governance headings. The Chinese ESG applies to the whole country though: corporations, government agencies and individual citizens. Also, it is envisaged to be compulsory.

But compulsory does not mean that China is already a well-oiled machine executing Xi’s principles. The reality is that implementation is highly fragmented across regions and agencies.

A good example may be the “social credit” system. The system is meant to discourage behaviors seen as creating negative externalities for others. This could be environmental pollution by a chemical plant or simply playing loud music in a subway. Both could reduce your credit rating (see here for example, Google translate may be needed).

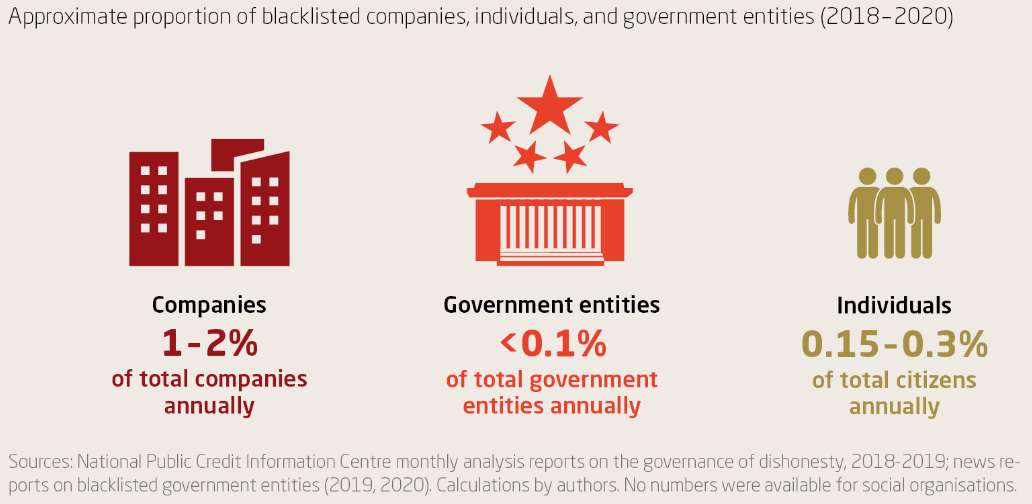

The exact standards often vary from one place to another. Local officials typically do not share Beijing’s lofty goals and are known to use the system to intimidate or extort people. Still, blacklisting and sanctions don’t seem to happen as commonly as perceived:

The 0.15-0.3% people (above-right) amount to 2-4 million blacklisted every year in China’s legal system. That is common enough to be concerning, at least to non-Chinese. There does exist a “forgiveness” process which allows you to apologize and have your come-to-Jesus moment at the CCP office. Reprieves are common.

The system is draconian given the public has no input and it is obviously authoritarian. But that’s not all it is.

For example, if you look at the business aspect of it, it is sort of in line with global sentiments around “predatory” corporate practices. Right here in the United States there are vocal demands that corporations promote “social good” in addition to earning profits.

It is the way China does it, through authoritarian fiat, and the extension to individuals, that we find most uncomfortable1.

But communist states have always seen it as relatively more acceptable if some people need to be thrown under the bus in pursuit of national objectives, in this case the “rejuvenation” of China. Xi’s ESG principles are meant to achieve that full rejuvenation by 2049 as per official pronouncements.

At the top level these principles relate to national governance:

Unchallenged CCP authority and continued relevance

Dominating the narrative

These are the most non-negotiable. The remaining goals could be listed as:

Contribute positively to national power

Avoid monopolistic practices

Transparent regulation (!)

Promote “green” environmental policies

Be ethical, socially responsible and avoid negative externalities

What you have is a mix of standard progressivism, technocratic governance and ruthless authoritarianism. It follows then that you can find all of these in China’s institutions.

There exists a highly technocratic section of the bureaucracy which is genuinely trying to build a modern legal system for the business economy. They scour the world for the best company laws and then patch them together. Thus China’s official accounting standards are among the toughest in the world and so are their listing requirements on exchanges. It is a different matter that the standards are often not followed and enforcement is spotty.

But just as China’s shiny high-tech corporations co-exist with state owned enterprises (SOEs), technocratic agencies also must co-exist with draconian, communist institutions. The draconian part has become more well-defined now i.e. Xi Jinping and his close advisors (the “high command”). Other CCP leaders simply try to please him and try not to get on his wrong side.

Xi and co don’t see themselves as oppressive though. Instead, they feel they bear a paternal responsibility to China’s progress which they cannot discharge without unconditional obedience. Some of the worst excesses arise from this paternalism. E.g. the Uighur people are seen as having “fallen behind” and so they must involuntarily reside in “special schools” until they have “caught up”.

The wrongs of the tech industry

Yet, it is illuminating to think of China’s tech crackdown within Xi’s ESG framework.

The first, most obvious issue is that consumer internet giants, the world over, are implicated in monopolistic behavior.

We know this is seen as a problem in the US. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) together with 46 states has sued Facebook and has three other lawsuits pending against Google. Washington DC has filed one against Amazon. As per witness testimony, the problems seem quite serious e.g. here is a seller’s anecdote about being shut out by Amazon because he dared to offer lower prices elsewhere. Such monopolistic practices are worse in developing countries and China is no exception.

The similarity ends there. In America, antitrust lawsuits are a contest between giants2: the Federal government on one hand and large corporations on the other. The government has to build a case and convince an unbiased party viz. the judges. Appeals are common, occasionally all the way to the Supreme Court. The legal system iterates both sides towards reasonable solutions.

There is no level playing field in China. You can’t really appeal and especially not publicly - the draconian part of the state ensures that. No one is safe from being “disappeared” as Jack Ma learnt, perhaps to his surprise. This creates considerable risk for investors if there is even a hint that the government is displeased.

Beyond antitrust, Xi sees problems with consumer tech as to its place in China’s overall rise.

Consumer internet makes money, yes, a lot of it. But Xi and his coterie have concluded that it does not add value in the sense of national power. There is little new technology/IP created except in the area of customer intelligence - which they don’t see as valuable. So, if China’s brightest minds join Alibaba then that brainpower doesn’t go into building the real high tech economy: meaning artificial intelligence, semiconductor chips, quantum computing and high-tech machinery. As per the “digital China” vision of the latest five year plan, this is where Xi’s emphasis is.

He wants to see some resource re-allocation from the consumer internet to the “industrial internet”. This places more focus on things like B2B info-highways and cloud computing. They will contribute to national power while B2C platforms will not.

B2C platforms will not be killed, but they will be hamstrung and so prevented from reaching their natural market size.

Additionally, under Xi-thought, selling more products to the same consumers is “rent-seeking” and so not exactly socially responsible. President Xi sees the US as a declining nation partly due to this rent-seeking and the obsession with social media and “financialization”. Hypothetically one could counter Xi by saying that China itself is highly financialized given its enormous corporate debt load. But that’s probably not how he understands the term. In his mind, financialization means that American energy is overly focused on financial innovation.

I am sure the reader can appreciate that there are many people right here in the US who would completely agree with Xi.

Which brings us to Alibaba and Jack Ma. Prior to ending up in Xi’s doghouse, Ma spoke on the need for regulatory reform at the star-studded Bund finance summit last October. He appears to have been in kamikaze mode. With heads of Chinese state banks and the PBOC in attendance he said that China’s banks have a “pawnshop mentality” and financial innovation is needed. This lecture did not go down well3.

Aside from business issues, Jack Ma’s “impertinence” highlighted to Xi the political power of internet platforms. They evolve faster than the government and can potentially overwhelm censors. Already, many Chinese are able to get around censorship using online techniques. But playing cat and mouse with censors is one thing and losing control of the narrative is a whole other thing. Dominating the narrative is central to the Party’s authority.

Thus, the process that began with Jack Ma and Alibaba is now in full stride. I want to repeat again that antitrust is genuinely a motive. Xi does want to create transparent governance and clear rules of trade. But that is not the only fish he is frying here.

Enduring regulatory and geopolitical risks

However much Xi might want a transparent business regulatory state, the fact remains that no rules so made would apply to him or the high command.

This is not necessarily an issue. For example, various levels of top-level authoritarianism have existed together with flourishing markets in Dubai, Singapore and Taiwan. The difference is that China’s authoritarians are much more interventionist in their approach. Their ultimate goal is to restore (what they believe to be) China’s “rightful” place at the top of the world order. They must defeat the United States and it’s allies to get there.

The fluidity of this objective demands that the high command be unconstrained and interventionist.

But this means that China cannot meaningfully reduce regulatory risks in its capital markets. That would require institutions to become bigger than all men or at least lesser ambitions on the part of the leadership.

Consequences for Chinese companies are already there. China’s internet sector has barely delivered 50% returns in the last five years, while the S&P 500’s internet component is up 235%.

Chinese stocks have been repeatedly hit by drawdowns. The two largest (~ 50%) drawdowns being directly traceable to CCP policy. The most recent of course and the other in 2018. Back then, a wide-ranging crackdown on Tencent and its gaming software left a pall over the consumer tech industry, just as it is doing this week. In the same year, the Party’s well-documented strong-arming of foreign companies doing business in China became a geopolitical problem. Colliding with the isolationist President Trump, a tariff war duly erupted and still continues.

It is not that the CCP doesn’t see the importance of markets. It does. But markets are secondary to internal social objectives and enhancing China’s national power. Thus practices such as IP theft from foreign firms and forced technology transfers are allowed because they are deemed contributive to China’s national power.

A game changer has been the massive cyberattack on Microsoft early this year. The repercussions are probably not talked about enough by the media. But, for the first time ever, the European Union joined with the US and UK to formally accuse the Chinese government of being behind it. This is “act of war” stuff, except they didn’t put it in so many words.

On China investments

No emerging market by itself should be seen as a passive buy-and-forget type of investment because regulatory risks are large. But because such risks are mostly independent of each other, a basket of EM countries has a diversifying effect making the whole thing a reasonable passive investment.

But China is not just another developing country. It is so much bigger than other EMs that emerging market funds have a ~ 40% allocation to Chinese stocks. If one invests into these vehicles (e.g. EEM), one is taking on a lot of un-diversified China regulatory risk.

A sort of workaround could be to invest in an ex-China ETF (such as EMXC) and then a separate China fund to right-size the risk.

That’s a step in the right direction but I can’t say I love it. One problem is that China’s gravity strongly influences stocks in many EM countries (e.g. Taiwan) as well as developed countries like Australia and Japan. Neither are the US and EU immune. So a globally diversified portfolio has China exposure anyway, whether one explicitly allocates to Chinese stocks or not.

Because it is hard to diversify China risks, investors need to be active. By that I don’t mean one must do a lot of fundamental analysis like cash flows, projections, valuation metrics, charts and tables, all that yada yada.

The most important thing to do is keeping up with Xi Jinping-thought and I don’t mean that in jest.

In the China market, “Xi whisperers” do very well. The best China stock pickers tend to be regular readers of publications such as Qiushi (“seeking truth”) viz. the Communist Party bi-monthly magazine. Helpfully, this magazine and other Xi thoughts are made available in English. Why? They want foreign investors to allocate money in line with their thinking. The more investment dollars are put into companies that Xi likes, the more they will grow. Xi’s goals will be met and the stock will appreciate.

This is what Chinese officials mean when they hold forth on “mutual benefits” and “win-win” situations.

Other important releases such as five year plans are also useful in identifying business areas that may not be in line with Xi’s ESG principles.

For example, if one had kept up with Xi-thought, one would have known well in advance that the Party is not in favor of for-profit schools or video games. Here are excerpts from a 2018 publication where Xi explains his views on education:

(One can buy the whole book on Amazon for $9.99.)

This is hardly definitive to be sure, but Xi has a record of eventually eliminating things that bother him. Either that or Chinese regulators serve him ideas that they think he would find pleasurable.

Are China tech stocks a value-trap?

The question for investors now is whether or not the 50% drawdown in the tech sector is at least a short-term buying opportunity.

Well, I would be surprised if some of these firms did not recover partially. The Chinese government may regulate them but it makes no sense to kill the sector. Many of the anti-monopolist changes may even be good, providing a much-needed level playing field.

There is (rampant) speculation that regulators went too far. Many Chinese investors expect the “national team” i.e. government-linked financial institutions to step in and rescue the market. Losses in mainland Chinese markets have been less, but to compensate, the investors are overwhelmingly retail i.e. common people, so the CCP may balk at the idea of them losing more money.

At the same time, its hard to believe that valuations would go back up to where they were.

I think the Chinese government will dragoon internet platform into serving Xi’s goals better. Some like Alibaba already have capable “industrial internet” businesses (e.g. AliCloud) which may put them at an advantage. Others may use their deep pockets to diversify into hardware and other favored industries.

As a matter of fact, Alibaba’s CEO Daniel Zhang, wrote a letter to investors a few days ago dutifully singing praises of the “industrial internet”:

Alibaba will leverage its digitalization and intelligence-based technology capabilities, using leading global technology standards as benchmark, to contribute towards advancement of China’s industrial internet. The development of China’s industrial internet means every industry and sector will increasingly be driven by intelligence-based technology. We will continue to drive our Cloud strategy to create a mobile office platform for enterprises, invest in technology development, build out a robust middle platform, strengthen our ecosystem, and deliver quality service.

Chinese businesses are accustomed to the system, i.e. working with the government for mutual benefit. I trust that most will figure it out. Some will disappear or worse.

On the flip side there is a plethora of firms in “real” high tech sectors like semiconductors which are obvious beneficiaries. They also have the advantage of being smaller than the internet giants, which means capital inflows could inflate their stock prices considerably. They have done well recently:

A barbell approach with investments split equally between internet firms and hardware could be seen as a good play.

Risks for US investors

There are issues specific to US-based investors that people should keep in mind. China’s consumer internet sector has many ADR listings in the US (E.g. BABA, TCEHY), but the real hardware sector is accessible mainly through Hong Kong exchanges.

Further, US investors buying Chinese ADRs should be aware of their Variable Interest Entity (VIE) risk. VIE is an unpalatable truth hidden in plain sight: China does not allow its firms to list in the US without permission. But none of these ADRs actually have permission. So how come they are listed here? Ans: by creating shell companies in the Cayman Islands which through a series of contracts reflect the balance sheet of the actual Chinese firm. This has always been listed in the prospectuses of these ADR offerings, but who reads those, right?

Popular Chinese ADRs are only tenuously connected to the underlying corporation. For what its worth, the latest word is that the Chinese government is looking to formalize this VIE listing route rather than force a mass dissolution. That is nice to know, but I wouldn’t put my feet up until they put it in writing.

Yet another issue is wrangling between the US and China over audit requirements. The US has a quasi-governmental organization called the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) whose job is to inspect the audits of exchange listed companies. Last December Trump signed the “Holding Foreign Companies Accountable Act” which requires companies to establish that they are not owned or controlled by a foreign government and allow the PCAOB to review their financial audits. As per the act, Chinese firms must delist from US exchanges within three years if they do not submit to PCAOB inspections on-site in China.

A further nugget of truth is that audit has historically been a weak point with Chinese firms. Ergo, there could be more than a pile of skeletons and “state secrets” buried there.

Also, can Chinese firms really prove they are not controlled by the Chinese government? Now isn’t that a fascinating legal question!

Negotiations are continuing with China on allowing PCAOB access to mainland firms.

I’ll leave it to the reader’s imagination as to how well these are going.

Full Disclosure

I recently went long China A50 index futures and BABA. This is not a recommendation to try that at home.

Perhaps it is worth pondering here how fair is our system of credit score monitoring. It disproportionately impacts lower income groups people with little financial knowledge.

Typically the Left viewpoint is that the field is in fact tilted towards corporations because the government is “underfunded”. I think that is more than made up for by other leverage the government has as well as the tendency of federal courts to side with the government.

The rest of the speech was hardly benign either.

I'm a Chinese,you are a man who understanding china than me.